Ultimate Guide to Nondestructive Testing (NDT)

Essential Nondestructive Testing (NDT) Methods for Safe Inspections

Nondestructive Testing (NDT) refers to a group of analysis techniques used to evaluate the properties or integrity of a material, component, or structure without causing damage (A Guide to NDT – Non-destructive Testing | RS). Unlike destructive testing, which involves breaking or altering the test piece to examine its failure modes, NDT methods leave the tested object intact and functional. This is crucial in industries where maintaining the original part is essential for continued use or further analysis. One of the main advantages of NDT is that it preserves the safety and longevity of critical assets—we often take for granted that airplanes, bridges, and pipelines are safe, and behind the scenes NDT is a key factor ensuring that safety and reliability (Nondestructive Testing (NDT) Applications Across Industries). By detecting defects or irregularities early, NDT helps prevent failures, reduce downtime, and save costs, all while ensuring that components are not weakened by the inspection process.

Key NDT Methods

NDT encompasses a wide range of techniques, each suited to detecting certain types of flaws or material characteristics. Below we explain eight of the most commonly used NDT methods: Visual Testing, Ultrasonic Testing, Radiographic Testing, Eddy Current Testing, Magnetic Particle Testing, Acoustic Emission Testing, Dye Penetrant Testing, and Leak Testing. Each method has unique principles and applications:

Visual Testing (VT)

Visual Testing is the most basic NDT method, involving the direct examination of a component with the naked eye or with optical aids (Explore Nondestructive Testing (NDT) Methods for Industry Safety). Inspectors look for surface abnormalities such as cracks, corrosion, misalignment, or other visible damage. Tools like magnifying glasses, borescopes, or video inspection cameras can enhance a visual inspection, especially for hard-to-reach areas (A Guide to NDT – Non-destructive Testing | RS). Despite its simplicity, VT is often the first step in an inspection sequence because it can quickly identify obvious issues without any special equipment. Its effectiveness, however, is limited to surface defects and depends greatly on the inspector’s experience and lighting conditions.

Ultrasonic Testing (UT)

Ultrasonic Testing uses high-frequency sound waves to detect imperfections or measure thickness in materials (A Guide to NDT – Non-destructive Testing | RS). In UT, a transducer introduces ultrasonic pulses into the material; when these waves encounter a flaw or a boundary (like the back wall of the object), they reflect back and are recorded. By analyzing the echo pattern (time it takes for echoes to return and their amplitude), technicians can locate internal cracks, voids, or inclusions. One common UT technique is pulse-echo, where a single probe emits and receives the sound – the reflections reveal discontinuities within the part (Ultimate Guide to NDT: Methods, Tools, and Applications). UT is widely used for inspecting welds, structural metals, and composites because it can probe deep beneath the surface. It is also valued for thickness measurements (for example, checking pipe or tank wall thinning due to corrosion). The method requires couplant (gel or water) to transmit sound into the part, and it works best on homogeneous materials; complex geometries or coarse-grained metals can scatter sound and complicate interpretation.

Radiographic Testing (RT)

Radiographic Testing involves using X-rays or gamma rays to produce images of a component’s internal structure (Explore Nondestructive Testing (NDT) Methods for Industry Safety). In RT, the test object is placed between a radiation source and a detector (film or digital sensor). The penetrating radiation is absorbed to varying degrees by the material depending on its thickness and density; areas with flaws (like cracks or voids) will allow more radiation through, appearing as dark indications on the film or detector output. The result is a radiograph – essentially an X-ray image – revealing internal defects such as inclusions, porosity in welds, or cracks inside a solid part (Ultimate Guide to NDT: Methods, Tools, and Applications). Thinner or less dense sections show up darker, and thicker or denser areas lighter, creating a contrast that highlights anomalies. Radiography is commonly used on welds (to find internal cracks or lack of fusion), castings, and structural components. While RT can provide a permanent image record and detect hidden flaws, it has safety considerations (radiation hazards require strict controls) and typically needs longer inspection times. Advances like digital radiography and computed tomography (3D X-ray scanning) are making RT faster and more informative in modern applications.

Eddy Current Testing (ET)

Eddy Current Testing is an electromagnetic technique primarily for finding surface or near-surface defects in conductive materials (A Guide to NDT – Non-destructive Testing | RS). A coil carrying alternating current is brought near the metal surface, inducing circular electric currents (eddy currents) in the material. Defects or material property variations disrupt the flow of these eddy currents, which in turn changes the impedance of the coil. By measuring these impedance changes, inspectors can identify cracks, corrosion, or conductivity changes. ET is very sensitive to small cracks in or just beneath the surface, and it’s commonly applied in aircraft maintenance (for detecting cracks in fuselage or engine components) and tubing inspections (Explore Nondestructive Testing (NDT) Methods for Industry Safety) (Explore Nondestructive Testing (NDT) Methods for Industry Safety). It works on non-ferromagnetic metals (like aluminum, copper, stainless steel) and can even assess properties like hardness or heat treatment state. Eddy current probes can be designed in various shapes (pancake coils, bobbin coils) to suit different geometries, and an advantage of ET is that it requires minimal surface preparation and provides immediate feedback. However, ET is generally limited to conductive materials and shallow defect depths, and interpretation often requires skilled operators due to the influence of factors like lift-off, geometry, and material variations.

Magnetic Particle Testing (MT)

Magnetic Particle Testing (also called Magnetic Particle Inspection, MPI) is used to detect surface and slightly subsurface discontinuities in ferrous (magnetic) materials (Explore Nondestructive Testing (NDT) Methods for Industry Safety). The part is magnetized (using an electromagnet, permanent magnet, or electric current passed through or around the part), and if a crack or flaw is present, the magnetic field is disturbed and leaks out at the discontinuity. Finely milled iron particles (either dry powder or suspended in a liquid) are applied to the surface; these particles are attracted to areas of flux leakage, clustering to outline the crack or defect (A Guide to NDT – Non-destructive Testing | RS). Cracks show up as visible indications of particle buildup. MT can reveal cracks that are too tight or subtle to see visually, including those just below the surface. The method is relatively quick and great for ferrous welds, engine parts, fasteners, and structural components. It is often performed using fluorescent particles under ultraviolet light for higher sensitivity, or colored (visible) particles under white light. One important limitation is that the technique only works on magnetic materials and the part needs to be magnetized and then demagnetized after inspection. Additionally, very deep flaws (more than a few millimeters below the surface) may not produce a clear indication. Overall, MT is a highly effective, portable, and low-cost method for finding surface-breaking cracks in steel and iron.

(File:SSG. Zachery Doering, 49th Maintenance Squadront, performs a magnetic particle inspection at Holloman AFB.jpg – Wikimedia Commons) An NDT technician performing a magnetic particle inspection under ultraviolet light. The part is magnetized, and fluorescent particles reveal any cracks by gathering at leakage fields (glowing indications) (File:SSG. Zachery Doering, 49th Maintenance Squadront, performs a magnetic particle inspection at Holloman AFB.jpg – Wikimedia Commons) (File:SSG. Zachery Doering, 49th Maintenance Squadront, performs a magnetic particle inspection at Holloman AFB.jpg – Wikimedia Commons).

Acoustic Emission Testing (AE)

Acoustic Emission Testing involves listening for the short bursts of ultrasonic sound (acoustic emissions) that are spontaneously released by materials when they undergo stress or deformation (Ultimate Guide to NDT: Methods, Tools, and Applications) (Ultimate Guide to NDT: Methods, Tools, and Applications). When a crack grows, a fiber breaks, or any sudden strain event occurs in a material, it emits a pulse of sound energy. In AE testing, an array of sensitive piezoelectric sensors is attached to the structure (such as a tank, pressure vessel, or bridge) while it is subjected to stress (either in service, during a pressure test, or under controlled load). The timing and intensity of detected acoustic signals allow inspectors to locate the source of the emission and evaluate its significance. Essentially, the material is “monitored” for telling sounds of cracks forming or extending. Acoustic Emission is useful for continuous health monitoring — for example, detecting crack growth in a storage tank or fatigue in an aircraft structure in real time. It can cover large areas in a single test since sound waves travel from the source to multiple sensors. However, AE does not directly image a flaw; it only signals that a dynamic event (like a crack growing) has occurred (Explore Nondestructive Testing (NDT) Methods for Industry Safety). Interpretation can be complex, distinguishing between harmless noises (friction, impacts) and true structural emissions. Despite that, AE is a powerful tool for detecting active damage mechanisms and can indicate when and where attention is needed before a failure happens.

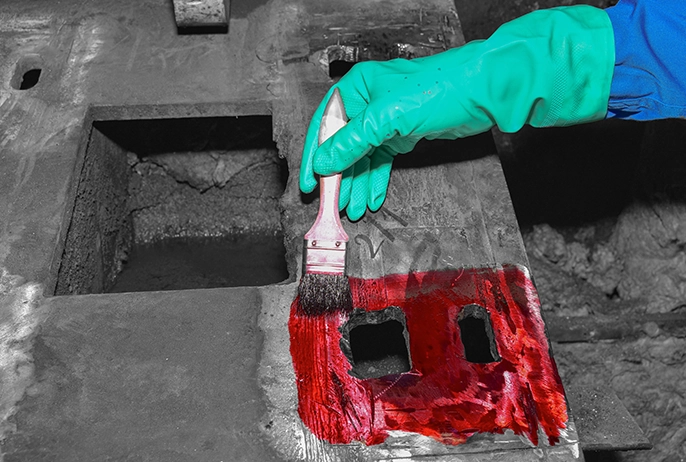

Dye Penetrant Testing (PT)

Dye Penetrant Testing (PT), also known as Liquid Penetrant Inspection, is a widely used, low-cost method for finding surface-breaking defects in non-porous materials. It’s essentially a visual enhancement technique: the inspector applies a liquid dye to the surface, which by capillary action seeps into cracks or voids open to the surface (A Guide to NDT – Non-destructive Testing | RS). After a sufficient dwell time, the excess surface penetrant is carefully removed, and a developer (a powder or solvent suspension) is applied. The developer draws out the trapped penetrant from defects, making a visible indication (a colored or fluorescent stain) against the developer’s background. Under proper lighting (visible light for red dye, or ultraviolet light for fluorescent dye), even tiny cracks become eye-catching. PT is excellent for finding fatigue cracks, seams, porosity, or grinding cracks on metals (including non-magnetic ones), plastics, ceramics, or glass. It’s commonly used on welded components, turbine blades, engine parts, and any critical surface that must be free of cracks. The advantages of PT include its sensitivity and simplicity – no expensive equipment is needed, and it can be applied to complex shapes. However, the surface must be very clean and free of paint or coatings (since those would block the penetrant), and the process is multi-step and somewhat messy due to chemicals. PT also cannot detect subsurface flaws – it only finds defects open to the surface. Proper ventilation and handling are required, especially with solvent-based penetrants. When done correctly, dye penetrant testing can reveal defects as fine as hairline fractures that might be missed by the naked eye.

(File:AmnHector Chacon, 49th Maintenance Squadron, performs a liquid penetrant inspection at Holloman AFB.jpg – Wikimedia Commons) Fluorescent dye penetrant inspection in progress. The inspector has applied a fluorescent penetrant to a metal component and is using ultraviolet light (blacklight) to inspect it. Cracks or surface defects would appear as bright glowing lines, indicating penetrant trapped in those flaws (A Guide to NDT – Non-destructive Testing | RS).

Leak Testing (LT)

Leak Testing is a method used to detect and locate leaks in sealed systems or components, such as pressure vessels, pipelines, tanks, or valves. There are various techniques for leak testing, ranging from simple to highly sensitive (Leak testing methods) (Leak testing methods). A common basic technique is the bubble test, where the test object is pressurized (with air or gas) and a soap solution is applied to suspect areas – escaping gas forms visible bubbles indicating leak sites. Another approach is pressure decay or vacuum decay: the item is pressurized or evacuated, and then monitored for a pressure change over time (a drop in pressure suggests a leak) (Explore Nondestructive Testing (NDT) Methods for Industry Safety). More sensitive methods use tracer gases: for example, filling the component with a tracer gas (like helium or hydrogen) and using detectors (mass spectrometers or specialized sensors) to sniff out any escaping tracer (Leak testing methods). Helium mass spectrometer testing is one of the most sensitive leak testing methods, capable of detecting extremely small leaks by measuring helium escaping from the test object. For certain applications, acoustic leak detection can be used: listening for the high-frequency sound of gas escaping through a small orifice using ultrasonic microphones. Each technique has its use case depending on the required sensitivity and the environment. Leak testing is crucial in industries like oil & gas (to ensure pipelines or valves don’t leak), HVAC (checking refrigerant lines), automotive (fuel and exhaust systems), and packaging (ensuring seals are intact). This method of NDT directly verifies containment integrity – a “pass/fail” type of test regarding whether fluids or gases remain sealed. While leak testing may not pinpoint a crack like other NDT methods do, it effectively tells you if a system is hermetic and where it might be leaking by the very nature of the escaping test medium (Explore Nondestructive Testing (NDT) Methods for Industry Safety).

Applications of NDT

NDT methods are employed across virtually every manufacturing and infrastructure industry to ensure safety and quality. By detecting defects early without harming components, NDT saves lives and costs, making it an indispensable part of maintenance and quality control. Here are some key industries and how they apply NDT:

Oil & Gas Industry

(File:Ultrasonicpipeline test.jpg – Wikimedia Commons) Ultrasonic inspection of a pipeline weld in the oil and gas industry. Here a technician uses an ultrasonic phased array device to scan a pipe weld for internal defects, ensuring the pipeline’s integrity (File:Ultrasonicpipeline test.jpg – Wikimedia Commons) (File:Ultrasonicpipeline test.jpg – Wikimedia Commons).

In the oil and gas sector, NDT is critical for preventing leaks, explosions, and environmental disasters. Equipment like pipelines, pressure vessels, storage tanks, and offshore platforms are routinely inspected using multiple NDT methods. For example, pipeline welds are tested with ultrasonic or radiographic methods to detect cracks or lack of fusion before the line is put into service. During operation, periodic inspections use ultrasonic thickness measurements to monitor corrosion or erosion thinning. Storage tanks (for fuel or chemicals) are inspected with methods like magnetic flux leakage (for floor corrosion) and ultrasonic testing (for wall thickness) as mandated by standards (e.g., API 653 requires regular tank inspections (Voliro) (Voliro)). In refineries, critical pressure vessels and heat exchangers undergo radiography or advanced ultrasonic (like phased array UT) to find flaws in welds or detect creep damage. Magnetic Particle Testing and Dye Penetrant Testing are commonly used on refinery piping or drilling equipment to find surface cracks (such as stress cracks around welds or threaded connections). Leak testing is also directly applied – for instance, after assembling a pipeline or tank, it might be pressurized and checked for leaks (hydrostatic tests or gas leak detection) to ensure all joints are sound. NDT in oil and gas not only helps in preventive maintenance (finding problems before they cause a leak) but also in repair verification (ensuring that a weld repair or a replaced part is sound). Given the hazardous nature of hydrocarbons, the industry relies heavily on NDT to maintain safety and compliance with regulations, thus protecting workers, the public, and the environment.

Aerospace Industry

Safety is paramount in aerospace, and NDT is integrated throughout the life cycle of aircraft—from manufacturing to regular maintenance inspections. In aircraft production, critical components (like turbine blades, airframe structures, landing gear, and composite parts) are inspected using NDT to ensure they are free of defects that could lead to failure. Ultrasonic and radiographic testing are often used to inspect composite materials and bonded structures for hidden delaminations or voids (Test NDT: Comparison of Nondestructive Vs. Destructive) (Test NDT: Comparison of Nondestructive Vs. Destructive). In-service aircraft undergo scheduled NDT inspections as part of maintenance programs: for example, Eddy Current Testing is widely used to detect surface cracks in aircraft skin, fastener holes, and wheels because it can cover large areas quickly and find tiny fatigue cracks that form from pressurization cycles. Magnetic Particle and Penetrant Testing are employed on engine parts and landing gear made of metal to find surface cracks (for instance, fluorescent penetrant inspections of turbine disks or fan blades to catch minute cracks before they grow). Aerospace NDT also uses advanced methods like thermography (infrared) to detect hidden damage in composites and Acoustic Emission monitoring for structural tests (listening for crack formation during stress tests on airframes). From the factory floor to routine overhauls, NDT ensures any flaw is detected and addressed long before it can pose a risk. This keeps aircraft safe at 30,000 feet by catching flaws before they become critical problems (Nondestructive Testing (NDT) Applications Across Industries). Beyond airplanes, the aerospace industry applies NDT to spacecraft, rockets, and satellites – for example, inspecting welds on rocket fuel tanks via radiography, or using ultrasonic scanning on solid rocket motors, since a single undetected defect could have catastrophic consequences. The rigorous standards and documentation in aerospace NDT (often following strict protocols like those from ASTM and aerospace manufacturers) reflect just how crucial these inspections are to flight safety.

Power Generation Industry

The power generation sector (including nuclear, fossil fuel, and wind power) relies on NDT to keep equipment functioning safely and efficiently. In nuclear power plants, NDT is heavily used to inspect reactor vessels, piping, steam generators, and turbine components because failures can be extremely costly and dangerous. Ultrasonic and radiographic testing check the integrity of welds in the reactor pressure vessel and piping (as required by codes like ASME Section V and XI). Eddy current testing is famously used in steam generators to scan thousands of heat exchanger tubes for corrosion or cracking without needing to remove them – a crucial task in nuclear plant maintenance. Acoustic emission systems might be used during periodic pressure tests of a containment vessel to detect any active crack growth. In fossil fuel (coal/gas) power plants, NDT monitors boiler tubes (ultrasonic thickness gauging for corrosion), turbine blades (FPI – fluorescent penetrant inspection – for fatigue cracks during overhauls), and generator rotors (ultrasonic or eddy current for detecting flaws). For wind turbines, NDT is increasingly important: large turbine blades (often composite materials) are inspected using ultrasonic or thermographic methods to find delaminations or bonding issues, and tower welds or gearbox components undergo magnetic particle or ultrasonics to ensure structural integrity. Electrical generation equipment also benefits from NDT; for example, infrared thermography scans electrical panels and transformers to find hot spots (incipient failures) without shutting them down. By catching material degradation like creep, fatigue, corrosion, or stress cracking early, NDT helps power plants avoid unplanned outages and extends the life of critical components. This industry also has to follow stringent standards – for instance, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) codes dictate regular NDT inspection intervals and techniques for pressure components in power plants, ensuring consistent application of best practices. In summary, from huge rotors in wind farms to nuclear reactor welds, NDT keeps the lights on by ensuring the reliability of power-generating infrastructure.

Automotive Industry

In automotive manufacturing and maintenance, NDT helps ensure the quality and safety of vehicles without sacrificing components for testing. Auto manufacturers use NDT techniques primarily for quality control of critical parts and joints. For instance, many engine and drivetrain components (castings, forgings, and weldments) are inspected before assembly. X-ray or CT (computed tomography) scanning is used on complex cast iron or aluminum castings (like engine blocks, cylinder heads, or transmission casings) to check for internal porosity or shrinkage cavities that could lead to failure (Application of NDT in The Automotive Industry – OnestopNDT) (How Is NDT Used in the Automotive Industry? – FujiNDTBlog). Ultrasonic testing and magnetic particle inspection are applied to steel parts like crankshafts, camshafts, gears, and suspension springs to detect internal cracks or surface discontinuities from the manufacturing process or heat treatment (Application of NDT in The Automotive Industry – OnestopNDT). Welds on car frames or critical joints (for example, on trucks or rail vehicles) may be inspected via ultrasonic or radiographic testing to ensure proper weld penetration and strength. In the maintenance and aftermarket context, mechanics might use simpler NDT methods, such as visual and penetrant inspections, to check for cracks in wheels, chassis components, or brake discs when a failure is suspected. The automotive industry also increasingly uses automated NDT systems for high-volume inspection: eddy current arrays can quickly scan machined parts for flaws, and laser or camera-based systems can detect surface defects on production lines in real-time. As automotive technology advances (e.g., introduction of carbon-fiber composites in vehicles or additive-manufactured metal parts), NDT techniques are adapted from aerospace to automotive needs to inspect these new materials. The goal in automotive NDT is to ensure reliability while keeping production efficient – finding that one defective part in a batch before it’s built into a car that goes on the road. By preventing defective components from being assembled and by verifying the quality of safety-critical parts, NDT contributes to vehicle safety and reduces costly recalls.

Maritime Industry

Maritime applications of NDT include the inspection of ships, submarines, and offshore structures (like oil rigs) to guard against structural failures in harsh marine environments. Ship hulls are subject to corrosion (especially in saltwater) and need regular NDT inspections. Ultrasonic thickness measurements are extensively performed on the steel plates of a ship’s hull, tanks, and decks to monitor for thinning due to corrosion; classification societies have requirements for how often different areas of a ship must be measured. Similarly, magnetic particle or penetrant testing is used to inspect welds on a ship’s structure and critical attachments (like crane foundations, davits, or rudder and propeller components) for fatigue cracks that develop over time. For underwater hull surveys, divers or robotic submersibles use NDT – for example, they might perform flooded-member detection on offshore platform legs (an ultrasonic technique to see if an underwater structural member has been breached and flooded internally). Acoustic emission monitoring can be applied to detect crack activity in high-stress areas of ships (though this is less common than other methods). In the construction and maintenance of offshore oil rigs, NDT is indispensable: welds on subsea pipelines and platform structures are inspected by radiography or automated UT; risers and mooring lines may be checked by electromagnetic methods for fatigue; and composite patches or repairs on rigs are verified by ultrasonic or thermographic methods. Leak testing is also vital in maritime settings – for instance, hatch covers of cargo holds are sometimes tested using ultrasonic leak detectors to ensure watertight seals. The maritime industry faces the extra challenge of performing NDT in difficult conditions (underwater, at sea, in confined spaces like ballast tanks), so techniques like remote visual inspection (using drones or ROVs with cameras) are increasingly popular to reduce the need for human entry into hazardous areas. By employing NDT, the maritime sector prevents structural failures at sea (which could lead to sinking or environmental pollution) and complies with international safety regulations. Whether it’s checking the integrity of a tanker’s hull or inspecting the welds on a cruise ship’s engine mount, NDT helps keep vessels seaworthy and safe.

NDT vs Destructive Testing

Both nondestructive and destructive testing methods are used to ensure materials and components meet quality and safety standards, but they have very different approaches and implications. Here we compare the two in terms of their advantages and disadvantages:

- Preservation of Components: NDT preserves the integrity of the tested component, allowing it to be used after inspection (Test NDT: Comparison of Nondestructive Vs. Destructive). Because NDT doesn’t harm the item, you don’t need to sacrifice samples – this is especially advantageous for expensive or uniquely fabricated parts. Destructive testing (DT), on the other hand, renders the test sample unusable by definition; you either destroy the part or induce damage to observe failure modes, which means that part is scrapped after testing (Test NDT: Comparison of Nondestructive Vs. Destructive). This makes DT impractical for items that are needed in service or are too costly to waste (you wouldn’t crash test every car coming off the assembly line, for example).

- Cost and Material Waste: Because NDT does not consume the part, it is generally more cost-effective when you need to test each production unit or maintain in-service equipment (Test NDT: Comparison of Nondestructive Vs. Destructive). DT typically requires additional samples specifically made for testing or sacrificing a few from a batch, which increases material costs (and in some cases, these sample parts must be manufactured to the same specs as the real product, adding expense). Furthermore, if you attempted to do DT on actual service components, you’d have to replace them, which is often far more expensive. In contrast, an NDT approach can test the actual item and then that item can continue to be used if it passes. That said, DT equipment and setups (like a tensile test machine or charpy impact tester) might be simpler or cheaper than some advanced NDT instruments, but the ongoing cost of destroyed samples typically outweighs that for production testing.

- Speed and Efficiency: NDT methods can usually be performed quickly and often on-site, minimizing downtime. In many cases, NDT inspections can be done in-place without disassembly and even while equipment is in service (for example, ultrasonic or thermal inspections while a machine is running) (What Is Destructive Testing? | How Is It Different From NDT?) (What Is Destructive Testing? | How Is It Different From NDT?). This means less operational interruption – a big economic benefit. Destructive tests often take more time because they involve taking specimens (sometimes requiring disassembly or cutting), preparing them, and then conducting the test which physically strains the sample to failure. Also, DT is usually done in a lab environment, not in the field, so there’s time lost in removing the part and transporting it or making test coupons. As a result, NDT generally offers faster turnaround and results, supporting more frequent inspections and proactive maintenance schedules (Test NDT: Comparison of Nondestructive Vs. Destructive) (Test NDT: Comparison of Nondestructive Vs. Destructive).

- Depth of Information: Destructive testing, by its nature, can provide direct and quantitative information about material performance – for example, the exact load at which a part breaks, its deformation characteristics, fracture type, or material microstructure after breakage. It’s very useful for material characterization (tensile strength, hardness, impact toughness, etc.) and understanding failure modes by examining a fracture surface or cross-section. NDT typically provides indirect indicators (like signals, images, or measurements that infer a defect or property) rather than a direct measurement of strength. For instance, an ultrasonic test might show a crack, but a destructive tensile test will show how that crack actually affects the ultimate strength of the part. Thus, DT is often used in research & development or when designing components to understand their limits, as well as in failure analysis when something has broken and you need to investigate why (Test NDT: Comparison of Nondestructive Vs. Destructive). NDT excels at in-service inspection and quality control (detecting manufacturing flaws or service-induced damage), but it usually cannot tell you exactly how much load a part can still take unless paired with engineering analysis.

- Sensitivity and Reliability: Modern NDT techniques are highly sensitive and can detect very small flaws – often with a precision that matches or exceeds what might be found by breaking a random sample (Test NDT: Comparison of Nondestructive Vs. Destructive). For example, ultrasonic or radiographic inspections might find a tiny internal crack that, in a destructive test, might only be discovered if the part happens to break there. However, NDT results require interpretation and can sometimes have false indications or miss defects if not done properly. Destructive tests are generally considered very reliable in revealing whether a part will hold up, because you actually push it to failure. But you can only do that to a few samples – it’s not feasible to destructively test every critical part in service. In practice, a combination is used: NDT to screen 100% of parts for flaws, and occasional destructive tests on sample coupons or retired parts to verify material performance and calibrate the NDT acceptance criteria.

- Use Cases: NDT is favored in scenarios where preserving the component is necessary – routine maintenance, final product inspection, and when testing all items (or large percentages) is desired. It’s also used when an object’s size or value makes destructive testing impossible (imagine destructively testing a whole bridge or an airplane wing – not practical!). Destructive testing is utilized for design validation, certification, and compliance (e.g., crash testing vehicles, drop testing packaging, proof testing of a batch sample), and for material property determination (like taking a steel coupon to pull in a tensile tester to get the yield strength) (Test NDT: Comparison of Nondestructive Vs. Destructive). It’s also common in welding procedure qualification – you weld sample coupons and then mechanically break them or section them to ensure the weld method is sound before using that procedure in production. In summary, NDT is a preventative and quality assurance tool, while DT is often a design and investigative tool.

- Safety Considerations: Both methods have safety aspects, but of different types. NDT is generally safer for the component and often for the operator, but some NDT methods involve hazardous materials or radiation (for example, radiography uses ionizing radiation, penetrant testing uses chemicals). Technicians must follow safety protocols (like radiation safety, proper ventilation, PPE for chemical handling, etc.) (Test NDT: Comparison of Nondestructive Vs. Destructive). Destructive testing can involve high forces, explosions (think of pressure testing something until burst), or other dangerous scenarios when a part fails violently, so those tests are done in controlled environments with safety measures in place (like barriers or remote controls). Importantly, from a system safety perspective, NDT allows inspection without compromising an in-service component’s safety. If you had to destructively test something in service to know its condition, that would clearly be counterproductive. NDT, by finding flaws, actually prevents accidents by guiding maintenance decisions while the component is still in operation (What Is Destructive Testing? | How Is It Different From NDT?). Destructive testing contributes to safety in a more indirect way – through design validation and standards development (the knowledge of how things fail, gleaned from DT, informs how and when we use NDT and what acceptance criteria to apply).

In practice, NDT and destructive testing are complementary. Industries typically employ NDT for regular inspection and quality control of individual items, and use destructive tests on sample materials or components to verify designs, validate NDT findings, or investigate failures. For example, a pipeline operator will use NDT to monitor the pipeline over time, but if a section is cut out, they might do a destructive lab analysis on that sample to understand the material’s remaining life or to validate that the NDT-reported defects were accurately assessed. The key trade-off is that NDT lets you inspect everything important routinely without harm, whereas DT gives you exact performance data but at the cost of the tested piece. In most safety-critical operations, the advantages of NDT (preserving components, cost-effectiveness, and ability to perform frequent checks) far outweigh the fact that it provides less direct performance data than destructive testing. With proper technique and multiple complementary NDT methods, engineers can confidently ensure integrity and only resort to destructive tests when necessary for additional information.

Regulatory Standards and Certifications

The practice of NDT in industry is governed by a host of standards and codes that ensure inspections are performed effectively and reliably. These standards cover both the methods and procedures of NDT and the qualification of personnel who perform the testing. Here is an overview of major organizations and standards relevant to NDT:

- ASME (American Society of Mechanical Engineers) – ASME publishes codes such as the Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code (BPVC) which includes Section V (Nondestructive Examination) detailing how NDT should be performed on pressure-retaining items, and Section XI for in-service inspection of nuclear power plant components. Many ASME codes are legally enforceable in jurisdictions (for example, in the U.S., pressure vessels must often meet ASME BPVC) (NDT Corner). These codes specify which NDT methods are required, acceptance criteria for flaws, and qualifications for NDT personnel for critical equipment like boilers, pressure piping (ASME B31.1 and B31.3 have NDT requirements for power and process piping (NDT Corner) (NDT Corner)), and nuclear reactors. Complying with ASME codes ensures a minimum safety level and consistency in NDT practices for high-risk equipment.

- API (American Petroleum Institute) – API develops standards for the oil and gas industry. Several API standards specifically address NDT inspection intervals and techniques for infrastructure in refineries and pipelines. For example, API 510 covers in-service inspection of pressure vessels, API 570 covers in-service inspection of piping systems, and API 653 covers inspection of aboveground storage tanks (NDT Corner) (NDT Corner). These standards outline how frequently inspections should occur (based on risk), what methods to use (e.g., API 653 details ultrasonic thickness checks for tank floors and walls, radiography for welds, etc.), and how to evaluate the results (accept/reject criteria for corrosion or flaws). Compliance with API standards is often mandated by regulators or adopted by companies to ensure safe operation of petrochemical facilities. API also offers certification for inspectors (like API 510/570/653 certified inspectors) who oversee these NDT programs.

- ASTM International (formerly American Society for Testing and Materials) – ASTM publishes hundreds of NDT method standards that detail how to perform specific examinations. These are often referred to as standard practices, guides, or test methods. For instance, ASTM E1444 is a standard practice for magnetic particle testing, ASTM E1417 is for liquid penetrant testing, ASTM E213 for ultrasonic testing of metal pipe and tubing, and so on (NDT Corner) (NDT Corner). ASTM standards ensure that when a technique is performed (say, magnetic particle inspection), it’s done in a consistent manner (with proper magnetization levels, particle application, lighting, etc.). They often include appendices with sample procedures and mandatory requirements such as penetrant dwell times or ultrasonic calibration steps. Many codes (ASME, API, military standards) will call out using ASTM standards for the actual execution of the test method. Following ASTM NDT standards helps guarantee a certain level of quality and repeatability in NDT results across different organizations and industries.

- ISO (International Organization for Standardization) – ISO issues standards that are globally recognized, including those for NDT methods and for NDT personnel certification. ISO 9712 is a key international standard for the qualification and certification of NDT personnel (NDT Corner). It defines a framework for independent certifying bodies to certify NDT technicians at Level I, II, or III in various methods (UT, RT, MT, PT, ET, etc.) through training, experience, and exams. Many countries base their national certification (like Canada’s CGSB, Europe’s PCN, etc.) on ISO 9712 to ensure NDT technicians are competent. ISO also has method standards (similar to ASTM) – for example, ISO 17638 for magnetic particle inspection of welds, ISO 3452 series for penetrant testing, ISO 17640 for ultrasonic examination of welds, etc., which align with European practices. Companies operating internationally often use ISO standards for consistency across borders.

- EN (European Norms) – In Europe, CEN (European Committee for Standardization) produces EN standards, many of which align with or adopt ISO standards for NDT. EN ISO 9712 is essentially the same as ISO 9712 for personnel. EN standards like EN 444 (radiographic exam of welds) or EN 583 (ultrasonic exam) were historically used; now most have an ISO equivalent. The aerospace sector in Europe has its own standards (e.g., EN 4179 for aerospace NDT personnel qualification, which is more employer-based and equivalent to NAS410 in the U.S.), ensuring aerospace NDT techs are qualified specifically for that industry.

- ASNT and Certification Programs – The American Society for Nondestructive Testing (ASNT) is a professional society that provides training guidelines and materials, but it does not set method standards (that’s left to ASTM) (NDT Corner). However, ASNT is known for its Recommended Practice SNT-TC-1A, which is a guideline for employers to establish in-house certification programs for NDT personnel. Many companies in the U.S. follow SNT-TC-1A, which allows them to train, examine, and certify their own NDT technicians. ASNT also offers a Central Certification Program (ACCP) and now an ISO 9712-compliant certification. Certification ensures that individuals conducting NDT have demonstrated a certain level of knowledge and skill, which is critical for the reliability of inspections.

- Other Industry-Specific Standards – Various industries and organizations have additional standards. For example, the American Welding Society (AWS) codes (like AWS D1.1 for structural welding) include NDT requirements for weld inspections, often referencing specific techniques or acceptance criteria for discontinuities (NDT Corner) (NDT Corner). The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in the U.S. mandates NDT procedures for aircraft maintenance (often using ASTM and aerospace OEM standards). The U.S. Department of Defense has MIL-STD documents (though many are now superseded by ASTM/ASME) for NDT in military applications. Similarly, the NACE (National Association of Corrosion Engineers) has standards for inspection related to corrosion (like inspecting coatings via NDT).

In summary, the NDT field is supported by a comprehensive framework of standards and codes that ensure inspections are carried out consistently and defects are evaluated to agreed-upon criteria. Organizations like API and ASME set the what, when, and acceptance of inspections in a certain industry, while standards from ASTM, ISO, etc., set the how of performing the inspections. Compliance with these standards is often mandatory (by law or contract) for critical applications such as pressure vessels, pipelines, aircraft, and infrastructure. Moreover, having certified NDT personnel (whether through ASNT, ISO 9712, or employer programs) is usually required to meet these standards. This ensures that whether an oil refinery in Texas or a power plant in Europe is being inspected, the technicians and the methods they use meet a rigorous baseline of quality and competence. Ultimately, these standards and certifications give confidence that NDT results are trustworthy and that public safety is protected through diligent inspection regimes.

Technological Advancements in NDT

Nondestructive testing continually evolves with technology. Innovations are making inspections faster, safer, more automated, and capable of detecting smaller flaws or handling complex structures. Here are some of the exciting technological advancements driving the future of NDT:

- Drones and Robotics: The use of robots and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) has revolutionized how inspections are carried out, especially in large-scale or hard-to-reach structures. Drones can be equipped with cameras for visual inspection, thermal sensors for IR thermography, ultrasonic probes, and even eddy current devices (Drones for NDT Inspections: Visual, Ultrasonic & Eddy Current …) (The Future of NDT: Emerging Technologies to Watch – CSI Structural Investigation). For example, drones are now used to perform ultrasonic thickness measurements on large storage tanks or flare stacks, eliminating the need for scaffolding and human climbers. They provide quick access to remote areas, like the top of wind turbines or under bridges, significantly reducing inspection time and cost (How UT drone inspections elevate safety and efficiency in NDT) (How UT drone inspections elevate safety and efficiency in NDT). Similarly, crawling robots (wall-climbing or pipeline crawlers) can carry NDT sensors along lengthy structures such as pipelines or inside ducts (The Future of NDT: Emerging Technologies to Watch – CSI Structural Investigation). Underwater ROVs (remotely operated vehicles) perform NDT on ship hulls and offshore platforms. The big advantage is increased safety (keeping inspectors off ropes or out of confined spaces) and coverage (robots can scan 100% of a surface where a human might do spot checks). These robots can operate in hazardous or inaccessible environments (radioactive areas, deep underwater, high elevations) and work longer hours without fatigue. With robotics, inspections that used to take days of preparation can be done in hours. As seen recently, specialized drones with built-in NDT payloads (like a drone carrying an ultrasonic thickness gauge in contact with a surface) are coming to market, and they are transforming NDT across industries by combining mobility with advanced sensors (How UT drone inspections elevate safety and efficiency in NDT) (How UT drone inspections elevate safety and efficiency in NDT).

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Data Analytics: AI and machine learning are becoming game-changers in NDT data interpretation. Modern NDT methods often produce vast amounts of data – think of high-resolution images from digital radiography or thousands of ultrasonic waveforms from a phased array scan. AI algorithms can be trained to recognize patterns associated with defects more quickly and consistently than a human. For instance, AI image analysis software can automatically flag potential crack indications on an X-ray or detect corrosion pitting in pipeline inspection images, reducing the burden on human inspectors and minimizing chances of human error (The Future of NDT: Emerging Technologies to Watch – CSI Structural Investigation) (The Future of NDT: Emerging Technologies to Watch – CSI Structural Investigation). Machine learning models can also optimize inspection parameters or fuse data from multiple NDT methods to improve flaw detection reliability. Another application is predictive maintenance: by continuously monitoring data (say from acoustic emission sensors or vibration monitors) and analyzing trends with AI, systems can predict when and where a failure is likely to occur, moving maintenance from a schedule-based approach to a condition-based approach (The Future of NDT: Emerging Technologies to Watch – CSI Structural Investigation) (The Future of NDT: Emerging Technologies to Watch – CSI Structural Investigation). An example would be using AI to analyze acoustic emission data from a bridge under load and warn if the pattern of emissions suggests a crack propagating, prompting an immediate detailed inspection. AI-assisted drones are also emerging – drones that not only gather data but use AI to navigate and identify areas of concern in real-time (Revolutionizing Industrial Inspections with AI-Powered Drones – ASNT Pulse) (Revolutionizing Industrial Inspections with AI-Powered Drones – ASNT Pulse). The fusion of AI with NDT equipment promises faster defect detection, improved accuracy (since AI can eliminate subjective calls and detect subtle indications), and the ability to handle the increasing volume of NDT data in modern inspections.

- Advanced Sensors and Imaging Techniques: New sensor technology is enhancing traditional NDT methods. Phased Array Ultrasonic Testing (PAUT) and Time-of-Flight Diffraction (TOFD) are advanced UT techniques now widely used: PAUT uses multiple elements in an array that can be electronically steered to scan and focus at different depths and angles, producing detailed cross-sectional images of a component and allowing faster coverage than single-probe UT (The Future of NDT: Emerging Technologies to Watch – CSI Structural Investigation) (The Future of NDT: Emerging Technologies to Watch – CSI Structural Investigation). TOFD uses diffraction of sound at crack tips to very accurately size cracks. These give inspectors far more precise information about flaw size and orientation than conventional UT. In radiography, digital detector arrays and computed radiography (imaging plates) have replaced film, enabling immediate image processing and enhancement (zooming, contrast adjustment) to better reveal indications. Computed Tomography (CT), essentially 3D X-ray imaging, is now used outside of medicine – for example, industrial CT scanners can inspect complex parts (like 3D-printed components or aerospace castings) in 3D, finding defects that might be obscured in a 2D radiograph (The Future of NDT: Emerging Technologies to Watch – CSI Structural Investigation) (The Future of NDT: Emerging Technologies to Watch – CSI Structural Investigation). On the electromagnetic side, Magnetic Flux Leakage (MFL) tools (commonly used for tank floor and pipeline scanning) are getting better with higher resolution sensors to map corrosion. Guided wave ultrasonics allow long-range screening of pipelines from a single test location, sending waves that travel tens of meters to find corrosion or cracks (great for insulated or buried pipes). In the realm of material characterization, laser shearography is an interferometric method that can detect surface-breaking and slightly subsurface defects by observing laser speckle patterns while a part is under slight stress – it’s used for composite aircraft panels and tires. Infrared thermography has improved with more sensitive IR cameras; it’s used for detecting delaminations in composites or poor insulation by observing thermal patterns. Additionally, embedded sensors (structural health monitoring systems) are being placed in structures to continuously monitor (for example, fiber optic strain gauges or acoustic sensors that constantly watch for changes). These advanced sensors and techniques allow for earlier detection of defects and more comprehensive inspections than were possible in the past, thereby improving safety.

- Digital Twins and Simulation: An emerging concept in maintenance is the use of Digital Twins – virtual models of an asset that are kept in sync with the real asset via sensor data and inspection results (The Future of NDT: Emerging Technologies to Watch – CSI Structural Investigation) (The Future of NDT: Emerging Technologies to Watch – CSI Structural Investigation). In NDT, this means that data from every inspection can feed into a digital replica of, say, a wind turbine or a bridge. This twin contains all known material flaws, thickness measurements, stress levels, etc. Engineers can simulate how defects might grow or how the structure would respond to loads in the future. The digital twin approach combined with NDT data allows for predictive forecasting – you can predict when a flaw will reach critical size and plan repairs just in time. It also helps in deciding optimal inspection intervals (focusing on hot-spots indicated by the simulation) and in what-if analysis (e.g., if corrosion rate continues, how many years until replacement is needed?). Essentially, digital twins turn periodic NDT data into a continuously updating picture of asset health, enabling smarter maintenance decisions and potentially extending asset life safely (The Future of NDT: Emerging Technologies to Watch – CSI Structural Investigation) (The Future of NDT: Emerging Technologies to Watch – CSI Structural Investigation).

- Automation and Integration: Many facilities are moving toward integrated NDT systems that combine various technologies. We see automated inspection systems in manufacturing: for example, robotic arms on production lines performing ultrasonic or eddy current scans on each part with minimal human intervention. In pipeline and tank inspections, automated crawling devices systematically scan and map out any defects, providing colored contour maps of wall thickness or crack locations. Software integration means NDT results can be fed directly into maintenance management systems. Also, reporting is improved – modern NDT devices often record data digitally, which can be automatically analyzed and compiled into reports, reducing human paperwork and error. There are even concepts of augmented reality for NDT: an inspector with AR glasses could see an overlay of previous inspection results or areas to examine on the actual component as they perform a test, enhancing thoroughness and accuracy.

- Drones with AI for Predictive Inspections: Bringing several advancements together, one of the most promising trends is AI-powered drones for industrial inspection. These drones could autonomously navigate and perform NDT, then analyze the data on the fly. Envision a refinery where a drone automatically flies to each structure, uses a combination of visual, thermal, and ultrasonic sensors, and returns with a complete diagnostic report – highlighting spots where corrosion is accelerating or where a crack might need monitoring. According to industry outlooks, within the next few years we expect a significant shift toward such smart inspection systems that dramatically cut down inspection times and improve safety by keeping personnel out of hazardous environments (Revolutionizing Industrial Inspections with AI-Powered Drones – ASNT Pulse) (Revolutionizing Industrial Inspections with AI-Powered Drones – ASNT Pulse). They will enable more frequent inspections (since they’re so fast and easy to deploy), moving industries closer to continuous surveillance of asset integrity rather than periodic checks.

Overall, technological advancements in NDT are making it more proactive, automated, and data-driven. Inspections that used to be labor-intensive can now be done with robots; interpretation that relied on an expert’s eye can be aided by AI; and techniques that found only big defects can now find tiny ones. These innovations allow for earlier detection of problems and more efficient maintenance strategies, which ultimately leads to safer operations and lower costs. The future of NDT will likely involve even greater integration with digital systems, real-time monitoring, and intelligent decision-making tools that can suggest optimal inspection and repair actions based on a wealth of data and analysis.

Best Practices for NDT Inspections

To reap the full benefits of nondestructive testing, inspections must be conducted with care, consistency, and regard for safety. Here are some best practices to ensure NDT processes are accurate, safe, and efficient:

- Proper Training and Certification: NDT is as much an art as a science, and the reliability of results depends heavily on the technician’s skill. It is vital that personnel performing inspections are well-trained in the methods they use and hold appropriate certifications (such as ASNT Level II/III, ISO 9712 certification, or employer-based qualifications) for those methods. Trained technicians know how to set up the equipment correctly, recognize true indications vs. false signals, and follow procedures precisely. They are also aware of the limitations of the method and when to call for additional or alternative testing. Continual education and re-certification keep technicians up-to-date with technique improvements and refresh their knowledge on standards and safety. Having a certified Level III or experienced specialist oversee the NDT program can ensure that procedures are appropriate and being followed, and that interpretation of results is verified when needed (for critical indications, second opinions are often a good idea).

- Follow Written Procedures and Standards: Each NDT method should be conducted according to a written procedure that complies with relevant standards or codes. Consistency is key for accurate results. The procedure will detail the step-by-step process: how to prepare the surface, calibration of equipment, specific technique (e.g., transducer frequency and angle for UT, or dwell time and developer for PT), and how to interpret and evaluate indications. Deviating from approved procedures can lead to missing a flaw or mischaracterizing it. For example, if a penetrant test procedure calls for a 10-minute dwell time and you rush it in 2 minutes, you may not give the dye enough time to enter fine cracks and thus could miss a defect. Best practice is to never shortcut the process and to use the proper reference standards or calibration blocks before and (if applicable) after testing to ensure equipment is working correctly. If a code or standard (like ASTM, ISO, or ASME) prescribes a certain technique for an application, those should be adhered to unless a qualified engineer approves a deviation. Standardized procedures also enable meaningful comparison of results over time. In summary: inspect as per the book – and if something in the field situation doesn’t match the procedure, revise the procedure (with proper approval) or use a qualified alternative, rather than ad-libbing on the fly.

- Equipment Inspection and Calibration: Before conducting any NDT, technicians should inspect their gear to ensure it’s in good working order (NDT Safety Protocols For Handling Equipment And Conducting Tests | NDT). Equipment that is damaged or out of calibration can lead to inaccurate readings or even hazards. Best practice includes regular calibration of instruments to traceable standards – for example, an ultrasonic flaw detector should be calibrated with known reference blocks to verify its accuracy in time/depth measurements (10 Tips for Effective Nondestructive Testing | EOXS). Many standards require calibration before each use or at set intervals. Magnetic particle yokes have a minimum lifting force that should be checked, radiographic equipment output is calibrated for exposure, eddy current devices use reference standards with known flaws to set sensitivity, etc. Additionally, performing function checks (like battery levels, cable continuity, UV light intensity for fluorescent inspections, and so on) ensures the equipment will perform during the inspection. Proper maintenance of equipment (cleaning, replacing suspect cables or transducers, software updates for advanced instruments) is also crucial. By treating NDT equipment with care and verifying its performance often, you maintain the integrity of your inspections. A small investment in calibration time prevents the huge cost of potentially unreliable results and repeated inspections.

- Surface Preparation: This is a frequently underrated aspect. The surface condition of the part can greatly affect certain NDT results. Best practice is to prepare the surface as required by the method – that could mean cleaning dirt, grease, or scale (which is especially important for PT and MT so indications aren’t masked) or removing paint if it interferes with the method (ultrasonics usually need direct contact with metal; eddy current can be distorted by non-conductive coatings if not accounted for). For radiography, knowing the surface condition is less critical for the result, but for visual inspection, good lighting and clean surfaces are a must to see fine details. In ultrasonic testing, a smooth surface helps the probe couple sound consistently. In short, ensure the part is in the right condition for testing: follow procedure requirements for pre-cleaning, paint removal, or sanding of welds if needed. After inspection, especially for penetrant or magnetic particle, clean the part of residual chemicals or particles and properly demagnetize if it was magnetized during test. This not only is good housekeeping but also prevents potential issues (e.g., residual penetrant chemicals causing problems in service or a magnetized part attracting debris later).

- Environmental and Process Control: Pay attention to the testing environment. Temperature, lighting, noise, or other environmental factors can influence both the inspection and the inspector. For penetrant and magnetic particle inspections, adequate lighting (with proper intensity and spectral range, UV-A for fluorescent methods) is mandated to be sure indications can be seen clearly. For example, a darkened area is required for fluorescent PT/MT, and UV lights must be checked for intensity and cleanliness. If doing a dye penetrant test in very cold or very hot conditions, the penetrant’s behavior changes, so one must use temperature-appropriate penetrants or ensure the part is within the specified temperature range (usually 40°F to 125°F for standard penetrants) or extend dwell times accordingly. Ultrasonic velocities vary slightly with temperature as well, though that’s usually minor for typical ranges. Noise and vibration can interfere with acoustic emission or ultrasonic listening devices, so try to minimize external disturbances (for instance, don’t run loud machinery nearby if you’re doing an acoustic emission test of a pressure vessel). For radiography, secure the area (as required by radiation safety) and ensure no movement during exposure that could blur the image. If you’re outdoors, weather can be an issue: avoid inspections in heavy rain or winds if it affects the method (UT couplant can wash away, RT film can get ruined, etc.). Essentially, create an environment that is conducive to the specific test – whether that means darkening an area, sheltering from weather, controlling temperature, or simply avoiding distractions that could cause a missed indication.

- Safety Protocols: NDT should never compromise the safety of personnel or the environment. Follow all relevant safety guidelines for the method:

- For radiographic testing, implement strict radiation safety: barricade the exposure area with the required exclusion zone, post warning signs and signals, use collimators or shields if possible, and ensure all personnel including the radiographer have appropriate dosimetry badges (NDT Safety Protocols For Handling Equipment And Conducting Tests | NDT). Only certified radiographic personnel should handle radioactive sources or X-ray equipment, and emergency procedures should be in place (e.g., in case a source gets stuck).

- For magnetic particle and penetrant testing, use appropriate PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) like gloves, safety glasses, and in case of aerosols or chemicals, maybe respirators (NDT Safety Protocols For Handling Equipment And Conducting Tests | NDT). Many penetrant materials are flammable and need ventilation; UV lights can harm eyes without protection. Ensure no open flames near flammable cleaners or developers. Skin contact with penetrants or magnetic inks should be minimized.

- Ultrasonic and eddy current methods are generally very safe, but even then, if using ultrasonic couplants, check they are non-toxic and clean up spills to prevent slips. High-voltage eddy current or electromagnetic equipment should be handled per electrical safety norms.

- When performing NDT at heights or in confined spaces (common in industrial sites), standard safety procedures for those conditions apply: harnesses and fall protection when at height, gas testing and permits for confined spaces, etc. For example, inspecting inside a large storage tank might require confined space entry protocols plus having a tripod and attendant.

- Electrical safety for equipment is important too – many NDT kits run on mains power; ensure cords are in good condition and use GFCI protection to prevent shocks, especially if working in damp environments.

- Finally, maintain a safe environment for those around: e.g., rope off an area beneath an inspector on a ladder (to avoid dropping tools on someone), or if doing a pressure test (which is a kind of destructive proof test) combined with acoustic emission, make sure the test area is cleared in case of a rupture.

Safety culture in NDT also means speaking up if a task is too hazardous. Perhaps a weld to inspect is in a spot that currently is unsafe to access – rather than risk it, best practice might be to postpone until proper scaffolding or other safety measures are in place. Remember that the purpose of NDT is to enhance safety, so it would be counterproductive to conduct an inspection in an unsafe manner.

- Documentation and Traceability: Good record-keeping is a hallmark of effective NDT programs. Each inspection should be documented with what was tested, which method and technique was used, calibration info, who did it (with their certification level), and the results and interpretation. If indications (flaws) are found, record their location (using sketches, photos, or precise measurements), size, orientation, and type. This not only supports any immediate repair decisions but also serves as a baseline for future inspections to see if a defect has grown. Many industries require traceability of NDT results: for example, aerospace and pressure vessel industries maintain NDT records for the life of the component. Using standardized report forms or digital databases ensures nothing is omitted. Photographic evidence (like attaching the actual radiograph or ultrasonic scan screenshots or thermo images) is extremely useful for back-reference. When possible, utilize digital tools: there are now software systems where you can log NDT findings on 3D models of the component. Consistent documentation also helps in audits (demonstrating compliance to standards) and in case a failure ever occurs, you have evidence of inspections that can be analyzed to improve processes (or to show due diligence). In summary, document everything relevant: what was done, how it was done, the outcome, and any recommendations (e.g., re-inspect in 6 months, or part is acceptable for service, or part rejected and removed).

- Integrity of Evaluation: Ensure that evaluation of indications is done against the proper acceptance criteria (often provided by codes or design specifications). An NDT technician should know when something is non-relevant (like a false indication or an acceptable minor scratch) versus a true defect that fails criteria. For borderline cases, best practice is to err on the side of safety: for instance, if an ultrasonic echo might be a flaw that’s just at the reject threshold, you might call for further evaluation (maybe use another method or have a Level III review it) rather than just dismiss it. Maintaining independence and integrity is important – there can be pressure in some cases to “pass” a part. Ethical NDT practice means reporting the facts of the inspection without bias. This is helped by having clear criteria and sometimes a second pair of eyes (for critical weld radiographs, it’s common to have a second reader interpretation).

- Continuous Improvement: Treat NDT as an evolving process. Gather feedback on false calls or missed flaws (hopefully rare) to improve techniques or training. If a leak occurred that NDT should have caught, investigate whether the method was appropriate or if procedures need tightening. Keep up with new NDT technologies as they become practical – sometimes adopting a new tool (like phased array UT instead of old single-probe UT) can greatly enhance productivity and defect detection. Also, rotate inspectors if possible to avoid complacency – a fresh set of eyes might catch something someone else overlooks due to familiarity.

By following these best practices – qualified people, strict procedures, well-maintained equipment, safety precautions, and thorough documentation – NDT inspections will be more reliable and effective. The goal is an NDT program that consistently provides accurate information about asset integrity with no accidents during the inspection process. In doing so, companies can make informed maintenance decisions, avoid unexpected failures, and ensure the safety of operations and personnel.

Conclusion

Nondestructive Testing is an indispensable pillar of modern industry, allowing us to ensure the safety and quality of materials and structures without causing them harm. We have seen how NDT differs from destructive testing in preserving components and enabling frequent, cost-effective inspections while still delivering crucial information about internal or hidden flaws. A variety of NDT methods – from visual inspection to advanced ultrasonic and radiographic techniques – empower inspectors to detect everything from microscopic cracks in an aircraft engine to corrosion thinning in miles of pipeline. These methods find application in diverse industries: oil and gas facilities prevent leaks and explosions by inspecting equipment regularly; aerospace manufacturers and airlines keep aircraft safe through rigorous NDT of every critical part; power plants avoid outages by monitoring turbines, boilers, and reactors; automotive companies ensure reliability of critical components; and maritime industries maintain ship hulls and offshore platforms against the relentless effects of corrosion and fatigue.

Underpinning all NDT work are robust standards and certification systems (ASME, API, ASTM, ISO, etc.) that guarantee inspections are done correctly and personnel are competent. Compliance with these standards ensures that an indication found in one part of the world is evaluated the same way in another, bringing consistency and trust to NDT results. Furthermore, technological advancements are rapidly pushing NDT capabilities forward. Drones, robotics, and automation are taking inspectors out of dangerous environments and covering more area in less time. Artificial intelligence and sophisticated data analysis are improving defect detection and enabling predictive maintenance by sifting through complex signals to find patterns. New sensor technologies and imaging techniques are revealing defects with greater clarity and depth than ever before, and concepts like digital twins are integrating NDT data into holistic asset management strategies. In the near future, we can expect NDT to become even more real-time and integrated – continuous monitoring systems might flag concerns instantaneously, and maintenance could become more anticipatory than reactive (Revolutionizing Industrial Inspections with AI-Powered Drones – ASNT Pulse) (Revolutionizing Industrial Inspections with AI-Powered Drones – ASNT Pulse).

The best practices outlined – from proper training and procedure compliance to ensuring safety and thorough documentation – provide a framework to maximize the effectiveness of NDT programs today. By rigorously adhering to these practices, industries ensure that NDT results lead to correct decisions and truly enhance safety.

The future of NDT looks bright and dynamic. We will likely see greater use of machine learning to interpret results, making NDT more accessible and reducing human error. Miniaturization and novel sensors may allow NDT to be performed in situ on previously untestable components (imagine tiny ultrasonic probes embedded in engine parts that report on the fly). Remote NDT and teleinspection could become common – an expert could be half a world away analyzing live data from a robot inspector on site. Also, NDT will play a key role in new fields like additive manufacturing (3D printed parts need careful inspection since traditional quality metrics may not apply) and in the inspection of new materials (like composites, ceramics, and alloys designed for extreme environments). Another growth area is likely the expansion of standards and certification to keep pace with technology – as methods like guided wave UT or laser shearography mature, formal standards will ensure they are applied consistently.

In conclusion, NDT enables us to “look inside” materials and structures in a safe, non-intrusive way, acting as a critical guardian for everything from infrastructure to vehicles. The ultimate guide to NDT is one that continues to be written as technology and techniques advance. However, the core principles remain the same: meticulous inspection, without destruction, to find the slightest hint of a problem before it becomes a hazard. By embracing both the time-tested methods and the cutting-edge innovations – and always adhering to high standards of quality and safety – industries will continue to rely on nondestructive testing as a cornerstone of safety and reliability. The ongoing evolution of NDT promises not only to uphold this role but to expand it, giving us ever greater confidence in the things we build and use every day.